Download full version in PDF (EN)

The results of France’s 2022 presidential elections saw the highest percentage of votes for the far-right in the country’s history. Although Emmanuel Macron won, there is a profound crisis of representativity, a consequent generational gap in voting as well as a banalization of far-right rhetoric that not only threaten France’s democracy but the viability of both European democracies and the EU.

Introduction

The second round of France’s presidential elections took place on April 24th with the unsurprising reconduction of a second mandate for President Emmanuel Macron against his far-right opponent, Marine Le Pen. Macron is the first president in twenty years to win reelection, following Jacques Chirac’s infamous victory against Le Pen’s father in 2002. Yet, never has the far-right reached such high scores in presidential elections, gathering approximately three million additional voters since 2017. Equally worrying, these elections have known the lowest electoral turnout in fifty years. France’s democracy has been in crisis for years, this article sets to explain some of its underpinnings and what it might entail for democracy in Europe and the survival of the EU.

A Representativity Crisis

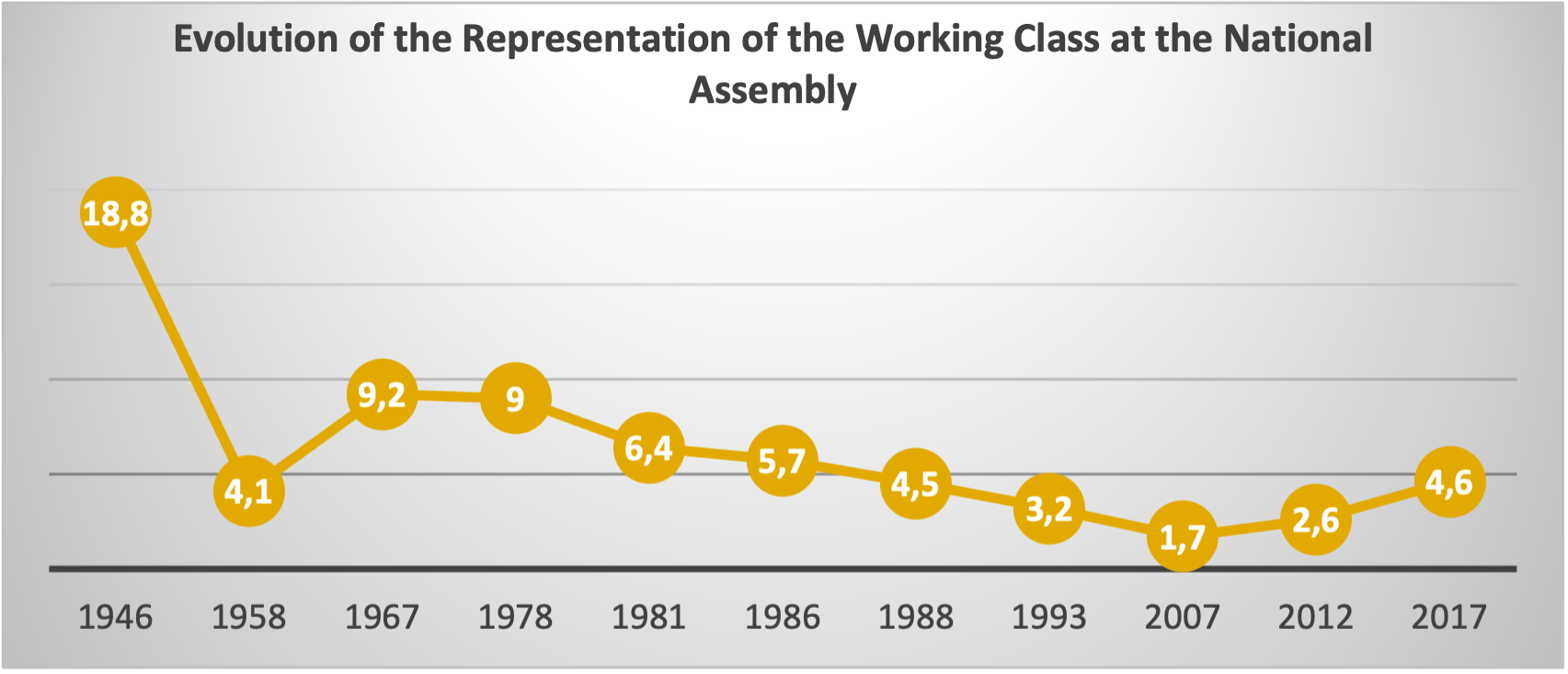

A recurrent issue in French politics and beyond is the disproportional representation of the working class by upper classes within the National Assembly. Although there is constant debating surrounding the issue of gender parity and the need for young people to hold office, the crucial idea of social, or class parity is rarely discussed. In 2017, Macron’s political party En Marche self-marketed as a promise for democratic renewal, yet the overrepresentation of higher socio-professional categories and the complete absence of working class’s parliamentarians was carried on in the Assembly. 76% of parliamentarians in 2017 either worked as executives or held intellectual professions, 4.4 times more than their representation within the French population. In the labor market, workers and non-managerial positions formed 50% of the active population in 2016.

This “France from below” initiated the Yellow Vests movement starting from November 2018 to demand a radical change in the way representative democracy works in France. Yet this was not always the case. Following World War II and the rise of the Communist Party, workers held 18.8 % of the Assembly’s seats.

Starting from the 1978 legislative elections with the end of the union of the Left, lower socioeconomic categories’ interests held less and less political space within State institutions.

The situation calls for two remarks. First, the absence of representation for the working class reflects the deeper problematic of what has become of left-wing parties that historically hosted the interests of the most disadvantaged. In France, the collapse of the Communist Party and the neoliberal shift of the Socialist Party left an electoral void that has been gradually filled by the far-right. The economic consequences of the Ukrainian war on the rise of energy and cereal prices, the consequent inflation European households have been bearing as well as the COVID-19 crisis prompted a profound reconsideration of the results of decades of neoliberal, austerity-driven policies, specifically considering drastic cuts to public services and climate change. Instead of favoring the Left, many French voters equated Marine Le Pen with the defense of poor and middle-class rural France and her criticism of Macron’s neo-liberal, Europeanist contempt towards le petit peuple.

Secondly, there is a considerable gap between the debate sparked by gender parity within politics and the absent question of the representation of poor and middle-class France. Per instance, no equivalence to the High Council for Gender Parity exists.

This undermined representativity regularly translates into abstentionism. In the second round of the 2022 presidential elections, 40% of households earning less than €1,250 per month did not vote compared to 32% in the €1,250-€2,000 category, 25% in the €2,000 - €3,000 category and 22% beyond for a national average of 28,01%. In contrast with 2017, abstention was at 25,44% with 34% of households earning less than €1,250 abstaining compared to 20% of households earning more than €3,000. In 2022, Marine Le Pen significantly progressed in the workers’ vote by eleven points (56% in 2017) and with employees by eleven points (46% in 2017).

A Generational Gap

Another problematic aspect is the correlation between voters’ age and voters’ priorities. Emmanuel Macron’s electorate is significantly composed of retirees. In the first round, 30% for the voters aged between 60 and 69 and 41% of voters aged more than 70 voted for Macron compared to only 17% and 9% for left candidate Jean-Luc Mélenchon whose program aims to keep retirement at the age of 60 and allocate 1000 euros per month to students. For voters of less than 35 years old, it is the latter who won by 30%. Notably, the Macron is ahead of Marine Le Pen with voters over 60 but stands behind the National Rally (RN)’s candidate in all other age categories, from 18 to 59. Considering Macron’s most controversial proposal is to rise the age of retirement to 65, it poses the problem of a president elected by inactive citizens. Fundamentally, it articulates the issue of generational fracture and the functioning of democracy within aging societies, specifically when older generations who benefited from social welfare, full employment, and retirement at the age of 60 favor socially hostile policies.

Additionally, the climate question, strongly present in the program of left candidates as Jean-Luc Mélenchon and Yannick Jadot, was lacking in that of the two presidential finalists.Macron’s government has been sanctioned for “climate inaction” while Le Pen wishes to reduce the share of renewable energies in the French energy mix, although the latest Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) report makes it central to halting climate change.

On a European scale, France is the only country to have missed its objectives in terms of renewable energies in 2020. Only 19.1% of its energy consumption is covered by renewables, instead of the 23% planned at the European level. In the Eurobarometer study carried out after the 2019 European elections, 45% of voters under 25 declared the need to tackle climate change drove their vote, compared to 34% of voters over 50 who rather focused on the preservation of certain social advantages (e.g., healthcare and pensions) as well as the fight against terrorism.These observations echo a survey highlighting that the hierarchy of French voters’ concerns is correlated with age. Protecting the environment is the primary concern of the 18-34 group, while those aged between 35- and 59-years old worry more about the purchasing power, and the 60 and beyond group cares principally for the preservation of certain social acquis.

Mainstreaming Far-Right Ideas

Since it first passed the first round of presidential elections in 2002 with 17,80% of votes, the RN consistently progressed in every election, scoring an all-time high of 41,46% in 2022. While some might find comfort in thinking the far-right party reached its glass-ceiling, the domination of its thematic in mainstream media and politics for decades has been significantly contributing to its rise.

Examining the last presidential term only, Macron’s government launched what it called an “anti-separatism campaign” in October 2020– culminating in the adoption of a law – consisting in the dissolution of CSOs, the shutdown of mosques and businesses deemed “communitarist”and thousands of police controls targeted at grassroots human rights organizations, radical Islamists, jihadists, traditionalists, conservatives or more or less practicing Muslims suspected of having some anti-government inclinations. Some children were even arrested on suspicion of promoting terrorism and placed in police custody for several hours (sometimes handcuffed) before being returned to their parents without further legal proceedings.

This “cultural war”, as qualified by minister of interior Gérald Darmanin, legitimized the pillars of the far-right’s discourse and praxis. It introduced concepts like “wokeism” and “islamoleftism” to delegitimize progressive narratives as anti-republican and apologetic of terrorism.These measures paralleled the reinforcement of police prerogatives at the expense of citizens’ liberties with the law on global security, another main thematic of the far-right. On a daily basis, mainstream media continue to echo the now-casual Islamophobic, anti-multicultural and anti-immigrant rhetoric with the continuous designation of common enemies placed outside of the national community, namely Blacks, Arabs and immigrants from the South.

Yet, the increasing tendency within European politics to appeal to far-right voters might be the death of the European ideal in itself as it entails politically advancing Euroscepticism. At the end of Macron’s second term, France will be left with two main opposition blocs (the RN and the driving force of the new coalition of the Left) which would both have called for disobedience to European treaties, both for a referendum on leaving the Union. Both are, for instance, highly critical of France’s involvement within NATO and the RN’s program clearly plans for a constitutional referendum on the primacy of French law over European law. In shorter terms, both the RN and the coalition of the Left (NUPES) cannot remain within the Union and apply their programs at the same time. This renders Frexit not only a possible but a plausible scenario for 2027.

Conclusion

The 2022 French presidential elections should serve as a warning to every established democracy regarding the risks of dismantling social acquis and embracing neoliberal policies. Socioeconomically disadvantaged citizens progressively turned away from electoral politics, and when they do vote, they increasingly support the far-right. In this sense, analyzing the vote for Marine Le Pen as a mere anger vote is reductionist. The elections’ results should also warn against playing into the hands of the far-right to attract voters and ensure an easy win. If France’s “republican dam” worked once again to prevent the extreme right from holding office, there is little insurance about the post-Macron era. The French elections were undoubtedly historical, but not simply because Macron won and Le Pen lost, but because this might have been the last election before a radical change occurs, both in French and European politics.